“My brother cried everyday and asked my mother ‘why aren’t we free?’ He’s too young to understand any of this. Two months ago, with another family from Syria we made a protest- we stopped eating and drinking for three days. My brother, my mother, two other kids, their parents and me. The naczelnik of the camp came and told us to stop or we would be deported. All we want is to be free.”

Jusef is 16 and tells his family’s story as its only English speaking member. Over the past year he has grown up very quickly: along with his mother and 9 year old brother they fled their war-torn country. Military occupation, bombing and fear for their lives left them no other choice, but Jusef does not want to talk about this place. It took them four months to get to Poland. First they reached Turkey from where they walked to Greece and crossed the border by swimming through the river Evros. From Greece they tried to go by plane to Denmark, where Jusef’s father who fled their country first, is waiting for them. Their plane was transiting through Warsaw when it turned out that they were without papers. This is where their trip ends, it is March 2012. According to Polish law crossing the border without permission is not a crime, but people who do so are considered to be a danger to national security. To prevent them from crossing more borders without papers (lest they choose to head west), the court sent Jusef and his family to Lesznowola, one of six closed detention centers in Poland where they spent the next 7 months.

“Lesznowola? I could write a book about my days in Lesznowola. I close my eyes and I see the cameras, the bars in the windows, the barb wires on the walls outside, electric fences, rewizje at 6 o’clock in the morning. Male guards with alcohol on their breaths checking my body, touching me,” recounts Leila. Leila is a women’s rights activist from Iran. Her organization, “One Million Signatures for the Repeal of Discriminatory Laws” is a grassroots movement that has been struggling to end legalized discrimination against women in Iran. Their struggle receives wide support from the international community: the campaign earned the Simone de Beauvoir Prize for Women’s Freedom and the Global Women’s Rights Award in 2009. Their campaign considered a threat to the Iranian authorities, more than 50 campaign members, including Leila, have been arrested and spent time in prison. This is why Leila had to leave Iran. In following the Dublin II Regulation[1] she was sent to Poland after she entered Europe (she had a Polish visa in her passport). Here, like Jusef and his family, the court sent her to the detention center in Lesznowola where she spent two months.

Ośrodki Strzeżone dla Cudzoziemców are administered by the Komenda Główna Straży Granicznej, which falls under the Ministry of the  Interior[2]. They are located at different points of the land and air border: Biała Podlaska, Białystok, Kętrzyn, Krosno Odrzańskie, Lesznowola (near Warsaw) and Przemyśl. By definition they are closed. Detainees are confined to cells, have little contact with the outside world, must conform to a prison-like regime, have limited access to medical and psychological care, are sent to isolation as punishment and are often subject to psychological, sexual and even physical violence. Detainees include men, women and children of all ages, and can be held in Ośrodki Strzeżone for up to one year. They refer to these centers as prisons. In fact, kadra Straży Granicznej obsługująca ośrodki jest szkolona przez służbę więzienną and in places like Białystok, the ośrodek strzeżony is located within the compounds of the local areszt śledczy.

Interior[2]. They are located at different points of the land and air border: Biała Podlaska, Białystok, Kętrzyn, Krosno Odrzańskie, Lesznowola (near Warsaw) and Przemyśl. By definition they are closed. Detainees are confined to cells, have little contact with the outside world, must conform to a prison-like regime, have limited access to medical and psychological care, are sent to isolation as punishment and are often subject to psychological, sexual and even physical violence. Detainees include men, women and children of all ages, and can be held in Ośrodki Strzeżone for up to one year. They refer to these centers as prisons. In fact, kadra Straży Granicznej obsługująca ośrodki jest szkolona przez służbę więzienną and in places like Białystok, the ośrodek strzeżony is located within the compounds of the local areszt śledczy.

In 2011, the Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej (SIP) published a report entitled, “Przestrzeganie praw cudzoziemców umieszczonych w ośrodkach strzeżonych. Raport z monitoringu”. Among numerous case studies documenting stories of people held in detention they mention that of a six year old girl from Georgia, zamkniętej w ośrodku w Przemyślu. Dziewczynka „przejawiała zachowania świadczące o początkach psychozy: często nieadekwatnie do sytuacji reagowała silnym i długotrwałym śmiechem, w innych momentach płakała nie mogąc się opanować. […] Często krzyczała, ‘ja tu nie chcę być, chcę stąd wyjść’, wskakiwała na meble, szarpała kraty w oknach. […] Pomimo przeprowadzenia badania, szczegółowego opisania sytuacji i skierowania do Sądu Rejonowego w Przemyślu sporządzonej przez psychologa opinii wraz z wnioskiem o zwolnienie dziecka i matki z ośrodka strzeżonego, sąd postanowił przedłużyć ich pobyt w placówce detencyjnej[3].”

People held in Polish detention camps learn quickly what it is to be “illegal people”. Criminalization means they are treated like humans of a second category. Denied basic rights, subject to violence. It is no surprise that hunger strikes motywowane oporem wobec więziennego rygoru i warunków panujących w ośrodkach strzeżonych wybuchają tam systematycznie. The majority of these protests however, like Jusef’s, his mother’s, his 9-year-old brother’s and the Syrian family’s never make news, or force the Straż Graniczna or MSW to change its policies.

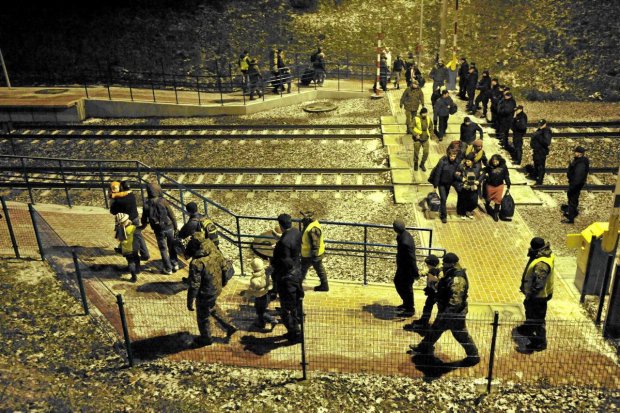

Na przełomie września i października, a Polish-French grassroots no-border group visited four of the closed detention centers in Poland. They were able to meet separately with detainees and border guards. One of their primary findings was that hunger strikes break out often and that standard practice is to place strikers in isolation and keep them there until they start eating. While visiting the camps, the group learned that detainees were striking in a few camps at the same time. They helped the strikers exchange contacts and write down a list of common demands. Soon, the amount of people striking grew as did the Polish support group. In mid October, there were over 70 women and men on hunger strike for over 8 days. In Przemyśl, Badri Kadrava refused food for 35 days until out of desperation he attempted to slit his veins while in isolation. Detainees in Białystok experienced the worst retaliation on the part of border guards. Hunger strikers reported being separated from those not on strike, having their right to use the phone restricted and being subdued using tazers. There were 8 people in isolation in Białystok.

SIP’s 2011 report concluded with recommendations that were verbatim to the striker’s demands. The rerport’s authors found that „ustawodawca traktuje cudzoziemców przebywających w ośrodkach strzeżonych w sposób bardzo zbliżony do postępowania wobec osób przebywających w więzieniach,” and that many of the restrictions nie znajduje żadnego racjonalnego uzasadnienia, „biorąc pod uwagę fakt, że mamy do czynienia z osobami, które nie popełniły przestępstwa i nie stwarzają co do zasady zagrożenia dla bezpieczeństwa naszego państwa.” Commenting the hunger strike on TVP info, prezes SIPu, Witold Klaus told reporters that SG ignored the report i nie ustosunkowała się do zawartych w nim rekomendacji[4].

SIP’s 2011 report concluded with recommendations that were verbatim to the striker’s demands. The rerport’s authors found that „ustawodawca traktuje cudzoziemców przebywających w ośrodkach strzeżonych w sposób bardzo zbliżony do postępowania wobec osób przebywających w więzieniach,” and that many of the restrictions nie znajduje żadnego racjonalnego uzasadnienia, „biorąc pod uwagę fakt, że mamy do czynienia z osobami, które nie popełniły przestępstwa i nie stwarzają co do zasady zagrożenia dla bezpieczeństwa naszego państwa.” Commenting the hunger strike on TVP info, prezes SIPu, Witold Klaus told reporters that SG ignored the report i nie ustosunkowała się do zawartych w nim rekomendacji[4].

Soon after news of the coordinated strike broke, Minister spraw wewnętrznych Jacek Cichocki was asked to comment on the situation. He told reporters that the Border Guard was trying to convince the strikers to stop. “Nie ma tam problemów poza tym, że niektórym osobom pochodzenia gruzińskiego nie podoba się, że stosujemy wobec nich procedurę, a nie pozwalamy wyjeżdżać na Zachód,” Cichocki told reporters. Further, he explained that „musimy przestrzegać unijnych procedur, bo od tego zależy nasza wiarygodność jako ważnego kraju w systemie Schengen. Szef MSW podkreślił, że protest nie wynika z powodów złych warunków pobytu czy złego traktowania tych osób.”

W ślad za obroną wiarygodności w strefie Schengen idą od lat polskie media, co zwykle sprowadza się do a dehumanizing discourse concerning immigrants from poorer countries and those ravaged by war. „Afgańczycy pokochali Podlaskie. Szturmują zieloną granicę[5]”, „Augustów: Czeczeni wdarli się do Polski razem z Kirgizem[6]” i „Nielegalni imigranci znów wdarli się do Polski[7]”. Komendant Podlaskiego Oddziału Straży Granicznej, Pułkownik Leszek Czech explains that the largest group of immigrants who try to cross the Polish border are Afghanis. “I to dla mnie szczególnie niepokojące. To ludzie z kraju ogarniętego wojną, zwykle bez dokumentów. Mają prawo ubiegać się o status uchodźcy […] W tym czasie musimy ich karmić a przede wszystkim leczyć […] To wszystko obciąża budżet państwa[8]. Meanwhile only about 1.6% of asylum seekers receive refugee status in Poland.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees notes that in 2011, the UNHCR worked in situations of armed conflict more than ever before in its  60-year history. Most of the refugees under its mandate in 2011 were Afghanis; they are the largest group seeking asylum- 27 million people in 79 countries. It is hardly mentioned, with another celebration of national independence approaching, that today Poland is an occupying country. That an entire district in Afghanistan is under Polish military rule, and that there are large chances that those Afghanis who escape to Poland are running away from Polish bullets.

60-year history. Most of the refugees under its mandate in 2011 were Afghanis; they are the largest group seeking asylum- 27 million people in 79 countries. It is hardly mentioned, with another celebration of national independence approaching, that today Poland is an occupying country. That an entire district in Afghanistan is under Polish military rule, and that there are large chances that those Afghanis who escape to Poland are running away from Polish bullets.

“Szef MSW sugeruje jednak, że protestujący to najprawdopodobniej nie uchodźcy, ale osoby, które poszukują pracy na terenie Unii Europejskiej,” says TVP info. Does this explain why people who committed no crime are kept behind bars? Według danych GUSu, w 2011 roku z Polski wyjechało ok. 60 tys. mieszkańców[9]. Meanwhile, over 20 million Poles live currently on immigration around the world, which means that one out every three Poles in the world is an immigrant. The majority of Polish immigrants left- and continue to do so- escaping different moments in a long continuum of repressive dogmas: fascism, racism, state socialism, marshal law, shock therapy and today, privatization and the free market. Like Polish immigrants once, Leila, Jusef and his family had no option to enter Europe “legally”, no time to stand in a long line at a European consulate only to be refused a visa, and no simple ability to buy a Ryan Air flight through the internet.

According to the historical archives of the Muzeum Polskich Formacji Granicznych, during the years directly following World War II, thus a period of severe Stalinist repression, 1,200 000 osób przekroczyło granicę państwa polskiego legalnie, posiadając paszport. W tym samym czasie niecałe 50 milionów osób z bloku wszchodniego przekroczyło granice bez jakiegokolwiek pozwolenia. As note the archive’s authors, thanks to “coraz skuteczniejsze zabezpieczenie granicy, wprowadzenie pasów kontrolnych, wyrzutni rakietowych, płotów z drutu kolczastego, wież obserwacyjnych, psów służbowych itp. – sprawiło, że nielegalne przekroczenie granicy stało się praktycznie niemożliwe. Tylko nielicznym udało się uciec z kraju […]” Do we consider people who fled Poland without passports and visas during this period, to be „illegal” immigrants? In following which legal system does the Border Guard call these escapes “nielegalne przekroczenie granicy”? Despite a long history of migration, refugeeism, and with statistically every Pole having an immigrant for a family member, Poland is no safe haven for those looking for a better life. Instead, it has become an obedient guard dog on the new European frontier. From the Dublin II Regulation, Frontex headquarters in Warsaw and a system of six detention camps for foreigners across the country, to an appropriately dehumanizing discourse practiced by politicians and echoed in the media.

[1] The Dublin II Regulation is a law adopted by the EU in 2003 according to which people seeking asylum in the EU are only able to file an application in the first country they enter. The law was passed just before the expansion of the eastern border of the EU to include Poland and other countries, amidst fears from western member states that a new entry gate would open for mass immigration from the east.

[2] There are also 12 open refugee centers dispersed around the country that are managed by the Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców. Refugees seeking asylum can live (it is optional) in these camps for the duration of their procedure. Although people complain of overcrowding and substandard conditions, they are free to move about.

[3] http://www.interwencjaprawna.pl/docs/ARE-211-monitoring-osrodki-strzezone.pdf

[4] http://tvp.info/informacje/polska/uchodzcy-protestuja-w-polskich-osrodkach/8832074

[5] http://bialystok.gazeta.pl/bialystok/1,35241,11778254,Afganczycy_pokochali_Podlaskie__Szturmuja_zielona.html

[6] http://www.poranny.pl/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20120531/REGION99/120539918

[7] http://www.poranny.pl/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20120516/AGLOMERACJABIALOSTOCKA/120519629

[8] http://bialystok.gazeta.pl/bialystok/1,35241,11778254,Afganczycy_pokochali_Podlaskie__Szturmuja_zielona.html

[9] http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/LU_infor_o_rozm_i_kierunk_emigra_z_polski_w_latach_2004_2011.pdf